A visit to a distinguished distillery in Scotland reveals the exacting traditional processes of creating some of the world’s best whiskies.

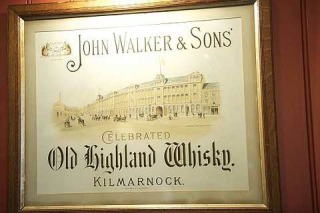

IN 1820, in Kilmarnock, Scotland, a 15-year-old boy named John Walker dreamt of blending the perfect whisky. Applying the same principles he had learnt from blending tea for his grocer’s shop to blending whisky, Walker began creating exclusive blends for valued customers who placed private orders at his shop.

“Walker’s Highland Whiskies” were soon created and launched to much acclaim. The business prospered and Walker’s reputation as an expert blender spread throughout the west of Scotland.

His aim was to create a flavour and quality that could be relied upon time and time again. In processing exceptional blends for his most prestigious customers, he firmly established his two dearly held blending values: quality and consistency. These values have underpinned Walker product developments ever since.

In 1850, Walker passed on his blending skills to his son Alexander who also became an expert blender, and perfected and copyrighted “Old Highland Whisky”, the precursor to the Johhnie Walker Black Label whisky.

It was the second whisky to emerge from the Walker stable, and like his father, Alexander, put a high value on the pursuit of excellence.

He once wrote: “We are determined to make our whisky, so far as quality is concerned, of such standards that nothing in the market shall come before it.”

Like a gourmet dish, a superior whisky’s success depends on the quality of the individual ingredients. Johnnie Walker’s grandsons, Alexander and George, searched long and hard for a distillery producing a malt of the stature they required for their blends. In 1893, they purchased Cardhu, in the Speyside countryside in Scotland, together with interests in several other distilleries, guaranteeing a supply of high quality ingredients for their whiskies.

The decision showed extraordinary foresight, and through this investment, the pair ensured that the taste and consistency of Johnnie Walker could be maintained far beyond their own lifetimes.

George masterminded the introduction of the Striding Man icon to support the launch of Red Label and Black Label in 1909 – an advertising symbol that epitomised the pioneering family spirit and one that soon became instantly recognisable to customers worldwide. By 1920, Johnnie Walker was sold in over 120 countries – and this was before Coca-Cola had even left the shores of America!

The groundbreaking global advertising campaign “Keep Walking” that began in 1999 pushed sales even more, and the journey, which began over 200 years ago, continues. Today, the Johnnie Walker blending team has the resources of over seven million cases of maturing whisky at its disposal, ensuring that each bottle purchased is characterised by quality and consistency of its founding father.

Masters of the art

Each year, it is the job of the highly experienced “masters of blending” at Johnnie Walker to select the specific casks that will achieve consistency of taste and quality. Like Alexander Walker before them, today’s master blending team not only possesses a natural talent, but receives comprehensive first class training to develop a master blender’s perceptive nose and palate.

Jim Beveridge, master of blending, explains the first steps in creating Johnnie Walker Blue Label whisky: “I’m looking for particular flavours and properties from the exceptional casks. These distinctive casks, which could be one or two in a couple of million, are usually spotted soon after they are distilled. They are then set aside and matured until they are at their absolute peak, however long that may be.”

Till today, the founder’s original values are rigorously applied when blending each whisky variant, he says.

“For example, every dram of Johnnie Walker Black Label you drink will have been blended from over 40 whiskies, each of which has been matured for a minimum of 12 years, some considerably longer.”

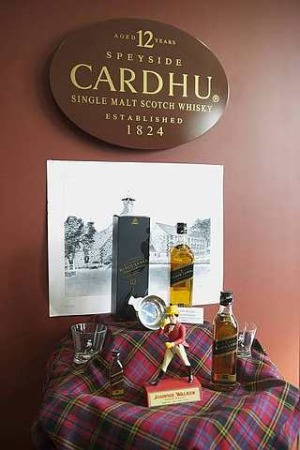

Three of the popular variants:Blue Label(top), Black Label (right)and Red Labelon display at the guest room of the Cardhu Distillery.

Three of the popular variants:Blue Label(top), Black Label (right)and Red Labelon display at the guest room of the Cardhu Distillery.Furthermore, Beveridge adds, “Your drink will have been two decades in the planning and drawn up from up to 700 casks, each matured in a slightly different way. This is an extremely complicated process for the master blenders, with satisfyingly complex results for the whisky enthusiast.”

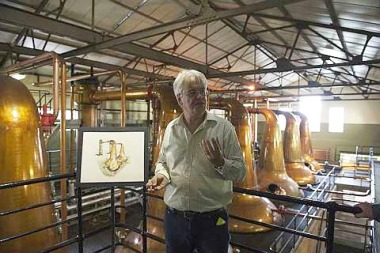

Every malt whisky is made from three ingredients: malted barley, water and yeast. The process is essentially the same at every distillery but it’s the small differences at each one that bring out the unique flavours, says Andy Miller, head of Cardhu distillery, which supplies most of the whisky variants used to create Johnnie Walker whiskies.

Distinguished distillery

In 1811, John and Helen Cumming sited their first still at Cardow Farm on Mannoch Hill, high above Scotland’s River Spey. At this location, spring water, naturally softened by rising up through a layer of peat, bubbled from the ground. It is reported that Helen distilled the first gallon of Cardhu, the only malt whisky to be pioneered by a woman.

For many years – indeed, until she was in her 90s! – Helen produced only the smallest quantity of malt whisky in Cardhu’s little still, as quality was her chief concern. Elizabeth Cumming, Helen’s daughter-in-law, took over the management of the distillery in 1872 after her husband died, and ran it with energy and foresight.

Under Elizabeth’s direction, a new piece of land was acquired on which the distillery was rebuilt in 1885. Sales of Cardhu tripled in the space of a few years, and by the end of the 19th century, Cardhu had attained a reputation for being one of Scotland’s top malt whisky distilleries.

Cardhu has made a unique contribution to the success of Johnnie Walker blends.

In 1893, when the Walker family wanted to guarantee the quality of their blends at a time of rapid growth, they negotiated the purchase of Cardhu Distillery from Elizabeth Cumming to secure supplies for blending. Elizabeth’s son, John Fleetwood Cumming, was appointed to the Johnnie Walker board.

His skill as a distiller complemented the talents of the Walker brothers, George and Alexander II, who brought both the artistry of blending and entrepreneurial drive to the company. Together, they made a team that ensured the growth in international popularity of the Johnnie Walker blends.

Malting

The first stage in the process of making malt whisky is malting the barley. Like most distilleries nowadays, this is one part of the process that Cardhu doesn’t do on site. Diageo, the world’s largest liquor company and owner of Cardhu now, also owns four “maltings” in Scotland that produce malt to suit the requirements of each distillery.

The purpose of malting is to break down the protein and cell wall material surrounding the starch to make the starch available for conversion into sugar, which is required for the next stage of the process.

First, the barley is soaked in water for two days. This really just “tricks” it into thinking that it is spring time and encourages it to grow. During this time, enzymes are activated that make the starch available for conversion into sugar later on at the distillery.

This process, called germination must be stopped after a certain amount of time so that the barley will not use up all the starch as it tries to grow. The only way to do this is by drying the barley.

It is at this drying stage that the whisky makers can begin to influence the flavour of the whisky. This is done by adding peat into the kiln; peat is a fuel made from decomposed plant material that, when it is burnt, gives off lovely smoky aromas.

“Smoke is no characteristic of a Speyside malt, though,” says Miller. “We will only use very small amounts of peat, or indeed no peat at all, when we are drying the malt for Cardhu.”

Milling and mashing

Once the malting process is complete the malted barley is taken to the distillery, where it is ground into a coarse flour called grist.

The purpose of mashing is to convert the starches in the malt into sugar, and then to extract the sugar from it.

The grist is put into a large container called the mash tun, along with hot water. The mashing takes about six hours in total, and for five of those hours, hot water is continuously added at increasing temperatures. The temperature starts at 64°C and is increased to 87°C. This is because some starches need higher temperatures to convert into sugar.

From every mash, the first 35,200 litres of liquid is drained off, says Miller. “This is a sugary water known as wort, and it will then go on to be fermented.”

Once all the liquid has been drained, the solids remaining is sent off to be made into cattle feed.

Fermentation and distillation

The wort, that sugary liquid from the mashing process, is placed into large containers called “washbacks”. Cardhu has 10 washbacks, says Miller. Into each is pumped 35,200 litres of wort, followed by yeast that will begin the fermentation process.

“We have a very long fermentation period, approximately 75 hours. The time of the fermentation is another thing that has an effect on the flavour of the whisky, so this time will vary at each distillery depending on the character they are looking for. After the fermentation, the liquid is now called wash and it is very similar to a strong beer,” explains Miller.

The distillation process takes place in stills. Cardhu uses the double distillation process, which is normal for Scotch malt whisky production. This is because: “The interaction of spirit vapour is one of the things, together with the shape and style of the still, that will have a major effect on the flavour of the whisky”.

Stills work very much like kettles: They are steam-fired inside, causing the liquid to boil. As it boils, all the vapours rise up and through the neck of the still into the “lye pipe” where it is cooled and turned back into a liquid in a condenser.

“In this first distillation, the liquid runs off at the ‘spirit safe’, and is known as low wine,” explains Miller, adding that this liquid requires to be distilled again in order to purify it.

The second distillation takes place in three smaller spirit stills. The process is very similar to the first distillation. The liquid boils, vapours rise through the neck of the still, along the lye pipe and down the back into the condenser. Again, the vapour is cooled and turned back into a liquid, and this liquid is drawn off at the spirit safe.

The main difference this time is that when the liquid is drawn off, it is divided into three parts: The head, which comprises almost pure alcohol that is too strong to use; the heart, that part that is sent for maturation; the tail, which comprises alcohol that is too weak to use.

The head and the tail are then mixed with the low wine from the first distillation process, and all of it goes back into the second distillation again, and the process continues.

“One thing that makes Cardhu unique is our lye pipe,” says Miller. “The lye pipe slopes slightly upwards. This means that only the lighter vapours will rise, and the rest will fall back into the still and be re-distilled, helping us to achieve our light character.

Maturation

Before any spirit can be called Scotch whisky, it has to be matured in Scotland, in an oak cask, for at least three years. Cardhu’s whiskies are usually matured for 12 years in oak casks that have been used to make American bourbon whisky.

Miller adds that: “We also mature a small amount in Spanish sherry casks – you might find the spirit taken from these casks in some of the award-winning Johnnie Walker blends.”

Every year the casks are maturing, though, the distillery loses about 2% of the content to evaporation. This is what is famously known as the “angels’ share”. Miller says this is not too much of a problem, as it is the much harsher spirit that evaporates, leaving behind a whisky that will become well-rounded and smooth.

Cardhu currently has 7,500 casks on site and produces 69,000 litres per week; the processing time from start to finish is approximately 95 hours.