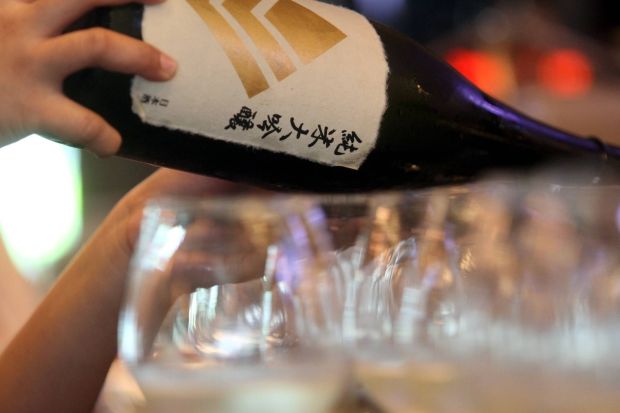

Our columnist finally tracks down someone to give him a crash course on Japan’s national spirit — sake.

I’VE ALWAYS been curious about sake. It was actually the first alcoholic beverage that I’d ever tasted, years ago, and I remember thinking how smooth and fragrant it was. Fast-forward more than 20 years later, I’ve grown to appreciate not just the flavour of sake, but also the culture and tradition of the drink in Japan.

However, it wasn’t until recently that I really got a chance to learn a bit more about Japan’s national alcoholic beverage, thanks to the visit of Nakashima Kozaemon, president of Nakashima Sake Brewing, brewers of Kozaemon sake.

Nakashima is a small sake brewery in the town of Mizunami in the mountainous area of Japan’s Gifu prefecture, and has a brewing history of over 300 years. The first Kozaemon (Nakashima Kozaemon Youshin) started brewing sake back in 1702 and today, his descendants have revived the family’s sake-brewing tradition.

Nakashima was in Kuala Lumpur to conduct a tasting of his company’s range of premium sakes, and was only too happy to give me a crash course in sake.

One of the first things you need to know about sake is that it is not a distilled spirit, but is fermented from Koji rice which, according to Nakashima, is specially grown for sake, and “not good for eating”.

Though Westerners tend to call it “rice wine”, it actually has more in common with beer than wine.

While the production of wine merely requires a simple fermentation of grapes and yeast, making sake is not quite so simple. Grapes already have residual sugar in them, so just adding yeast will start the fermentation process. However, rice doesn’t have any sugar so, for fermentation to start, the toji (sake master brewer) has to steam the rice, and then sprinkle a kind of mould (specifically, the micro-organism Aspergillus oryzae) that contains an enzyme which will then convert the starch in the rice into sugar (this has to be done at a high temperature).

“The yeast needs the sugar to make the alcohol. This multiple parallel fermentation of rice is one of the most difficult fermentation processes, and the alcohol (level) it makes is the highest amongst brewed alcohol,” said Nakashima in an interview at a restaurant in Bangsar South, Kuala Lumpur.

After fermentation is complete, the sake is then pasteurised and put into tanks where it is allowed to mature for at least nine months. However, unlike cognac or whisky, whereby the maturation process is supposed to impart more flavour to the liquid, sake is “rested” so that the rough, harsh taste of the newly made sake can mature into a softer, mellower and more well-balanced brew.

“The older the sake, the more well-balanced it is; and how long a sake is rested depends on the type of sake,” said Nakashima. “Our Jumnai Daiginjo is matured for two years, which is a very long time for a sake, but is necessary to make it more well-balanced.”

According to Nakashima, there are different grades of sake, ranging from the common Futsu-shu (or “ordinary sake”, akin to table wine), to the Tokutei meisho-shu (special premium sake).

“The way we classify sake depends on how fine the rice is milled or polished. The finer the rice used for the sake, the higher the grade of the sake,” he said. “For example, the rice polishing ratio for Kozaemon Junmai Daiginjo is 40%, which means 60% or the original rice is milled away, and only 40% is used for the fermentation.”

Like whisky, a pure source of water is equally important as water is used sometimes to lower the alcohol base volume (ABV) in the sake. Most undiluted sake comes in at about 20% ABV, which is then lowered to between 15% and 20%).

“Kozaemon takes its water from an underground spring. Natural water sources are the best, as the water is soft and natural, and won’t affect the yeast. Water from the cities won’t work because it contains chemicals, and will stink up the sake as well!” said Nakashima.

Sake can be drunk hot or cold, though it is usually taken hot when the sake is of a lower grade. Most of the higher-grade sake is usually taken chilled, as heating it up will only kill the subtle flavours and nuances in the delicately light spirit.

“Good sake like the Daiginjo should be drunk cold, because the flavours are very light and delicate. If you heat it up, these flavours will disappear,” he said.

But how does one distinguish between the different types of sake, especially if one does not read or understand Japanese? Simple: just check the label. If it contains the word “Junmai”, that means the sake is made purely from rice and water.

“If you don’t see ‘Junmai’, then it means that the sake also has distilled alcohol in it,” said Nakashima.

Then there is the category of the sake, such as Daiginjo or Ginjo, followed by the name of the rice used to make the sake. There are over 50 types of rice that are used for sake, and the best is Yamadashiki, which is known as the “king of sake rice”.

There are eight different varieties of high-grade sake, with Daiginjo (very special brew) occupying the highest position (with a rice polishing ratio of below 40%). Kozaemon currently produces 15 types of sake, and three types of Kozaemon fruit liqueurs. The jewel in the crown is the Kozaemon Junmai Daiginjo, which turned out to be my favourite amongst the six types of sake that I tasted.

It had a pleasant, fruity nose that reminded me of jackfruit, with some subtle rice notes in the background. On the palate, it has very delicate, subtly sweet rice and fruity flavours, and a lingering, faint jackfruit-like finish.

Other highlights included the excellent Kozaemon Junmai Ginjo Yamadanishiki and the Kozaemon Tokubetsu Junmai Miyamanishiki, as well as the Yuzu, a refreshingly sweet combination of sake and the juice from the Yuzu fruit (a grapefruit-like Japanese citrus fruit) that tasted great over ice.

Kozaemon Yuzu is a refreshingly sweet combination of sake and the juice from the Yuzufruit that tastes great over ice.

Kozaemon Yuzu is a refreshingly sweet combination of sake and the juice from the Yuzufruit that tastes great over ice.

According to Nakashima, sake is usually drunk together with food, and often, will taste better when paired with the right type of food (which, incidentally, doesn’t even have to be Japanese food).

“Sometimes when you try a sake, you might not like it at first. But then when you try it with food, you might change your mind,” said Nakashima.

Unfortunately, the consumption of sake in Japan has been on a gradual decline since the 1970s. In 1881, there were an estimated 26,826 breweries in existence; today, that number has dwindled to about 1,300 and is getting smaller every year with big companies swallowing up the smaller breweries.

“Younger Japanese don’t drink sake anymore, they prefer to have cheap, sweet cocktails or beer,” Nakashima lamented, then added that whatever the sake producers lose in the domestic market, they are making up for it by selling their product overseas.

“Yes, it is very sad that we are losing the culture, but sake will never disappear. Instead of focusing on the Japanese market alone, we are opening up to international markets. The market in Japan is growing smaller, but internationally, it is going up,” he concluded.

Kozaemon sake is currently being distributed in Malaysia by Chuan Huat F&B Trading. For more information, including where to find the sake, call their customer service centre (03-7846 8282).

Michael Cheang has fond memories of drinking sake for sake’s sake in Japan.